1978 - Made in Hungary 1.

Creators and works

1978-in the Car Engine in a series of twenty-four articles, he undertook nothing less than to present the - then - 150-year history of motor vehicle production in Hungary. The articles were written with 'completeness' and a textbook-like thoroughness that seems to have disappeared by now István Zsuppán from the pen. In all cases, the texts are presented in full text, with the images adapted to the needs of today's readers. You will find a gallery of images at the end of each post with the original, easy-to-read pages of the articles.

The next, second part of the article series here available at.

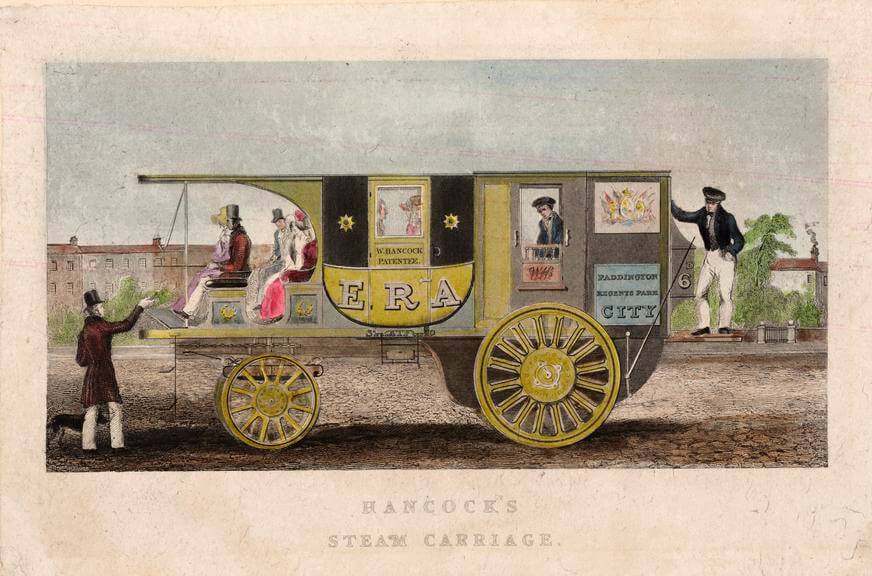

A Hancock steam-powered model from the 1830s - Image source: sciencemuseumgroup.org.uk

So here is the first introductory part of this series of articles, published in January 1978:

♠

With the following article, we are launching a new series in which we would like to outline the history of the Hungarian car industry. From time to time we have already published memoirs of some of the best-known figures of Hungarian car manufacturing, and of some almost forgotten Hungarian cars. Now, as part of a series, we are summarising and trying to be complete, we will present all those who actively participated in the creation of the self-propelled vehicle, the later automobile, in Hungary.

It is almost unbelievable that a small country like ours has such a long history of car manufacturing. How many people have tried to make cars over the ages! How many companies and factories have taken up or wanted to take up the automobile as part of their production profile, how many attempts have been made to set up a factory!

Hungarian professionals have always had the enthusiasm and creative spirit. The reasons for the fact that their attempts did not always lead to results must be sought in the economic and social conditions of the time.

In this series we focus on passenger car production, but occasionally we will also look at the trucks and other activities of a particular plant or factory.

To illustrate this, we have also tried to collect images that are little known or have never been published before.

We hope that our readers interested in old cars, the past of our automotive industry and the collectors of veteran cars, who are now also awakening in our country, will also find something new.

The initial attempts

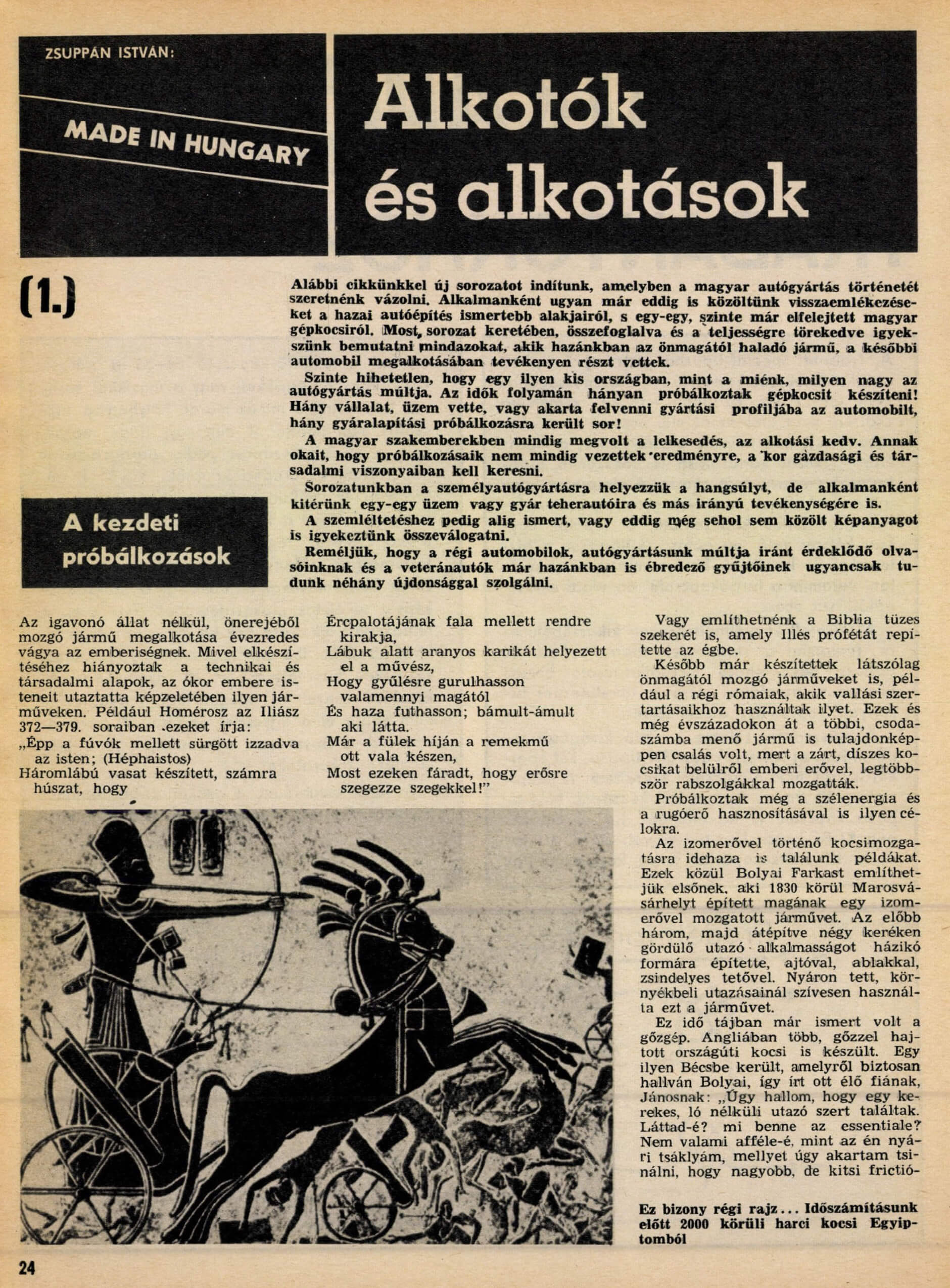

The creation of a vehicle that can move without a moving animal, on its own power, is a millennia-old human desire. Lacking the technical and social foundations to build them, ancient man used to transport his gods in such vehicles. Homer, for example, writes in lines 372-379 of the Iliad:

This is an old drawing...A war chariot from Egypt circa 2000 BC - image source: fount.aucegypt.edu

"The god was sweating by the winds; (Hephaestus)

He made an iron tripod, twenty in number, so that

It is regularly displayed next to the wall of his ore palace,

The artist has placed a cute ring under their feet,

So that all can roll to a meeting on their own

And to run home; stared and stared who saw it.

Without the ears, the masterpiece was ready,

Now they are weary to nail them strong with nails!"

Or we could mention the fiery chariot of the Bible, which carried the prophet Elijah to heaven.

Later on, apparently self-propelled vehicles were also made, for example by the ancient Romans, who used them for their religious ceremonies. These, and for centuries more, the other miraculous vehicles were actually a hoax, because the enclosed, ornate carriages were moved from the inside by human power, usually slaves.

Wind and spring power have also been tried for such purposes.

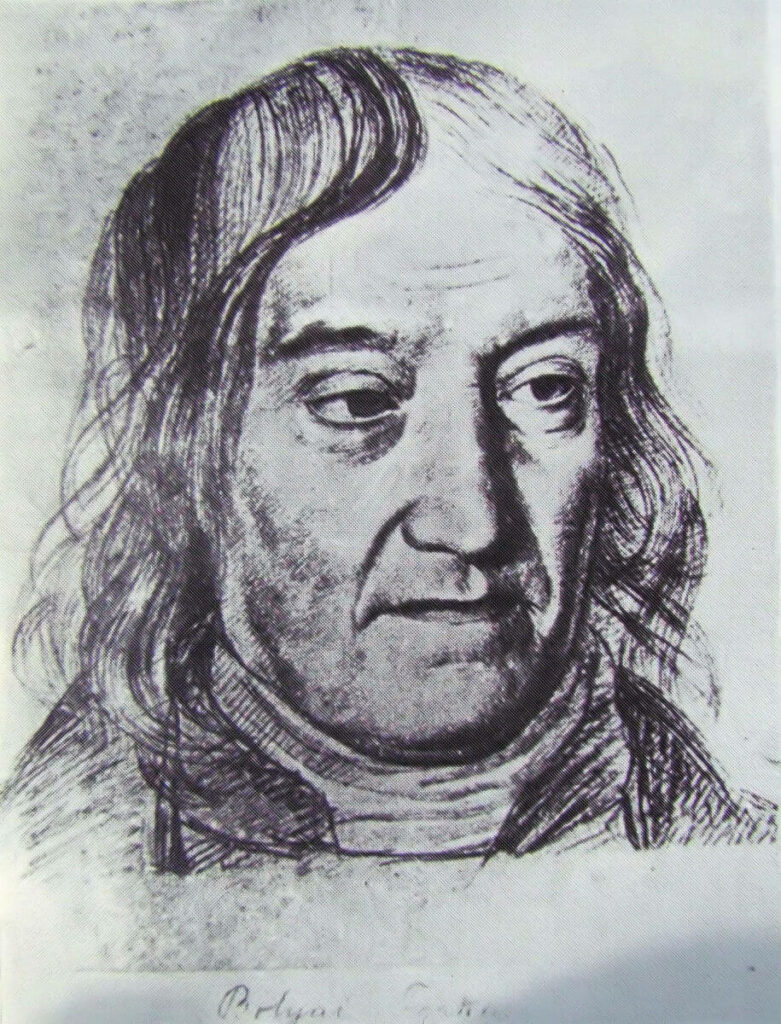

Bolyai Farkas - Image source: wikipédia

There are examples of muscle-powered driving at home. The first of these was Fark Bolyai, who built himself a muscle-powered vehicle around 1830. He built the travelling vehicle, first three wheels and later rebuilt on four, in the form of a cottage with a door, window and shingle roof. He liked to use this vehicle for his summer trips around the area.

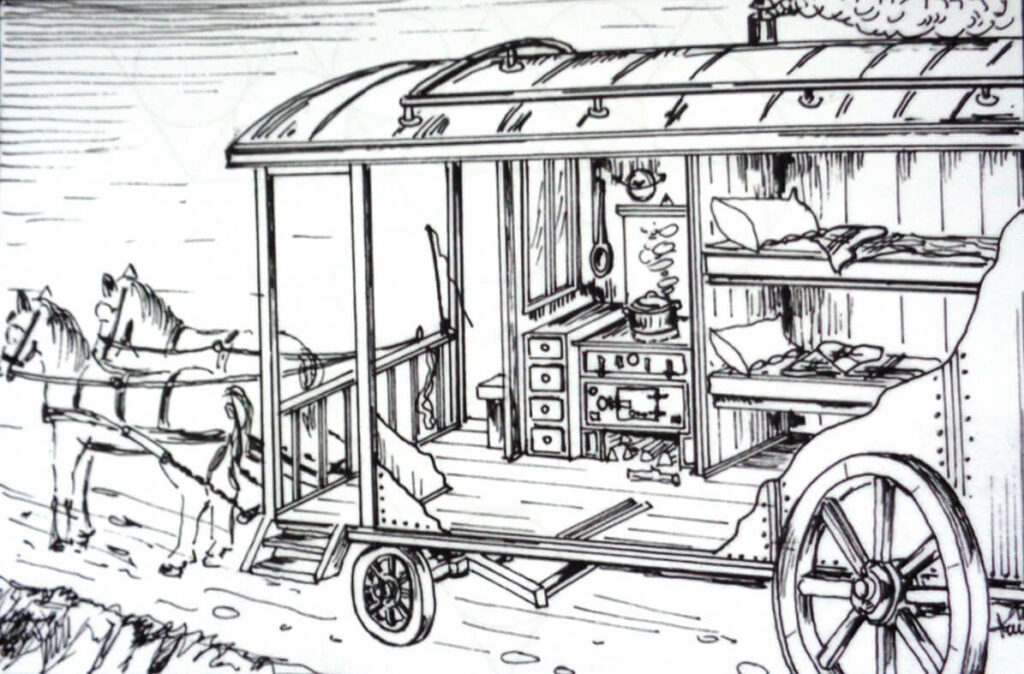

Kali Ellák's (1946-2013) reconstruction drawing of Bolyai's carriage house - image source: www.e-nepujsag.ro

By this time, the steam engine was already known. Several steam-powered road cars were made in England. One of these came to Vienna, of which Bolyai, no doubt hearing of it, wrote to his son John, who was living there. Have you seen what is essential in it? Is it not something like my summer sledge, which I wanted to make by standing on wheels of a larger but small size, with a foot and sometimes a stick? (could be operated). I'd like to know if you have one there in Vienna."

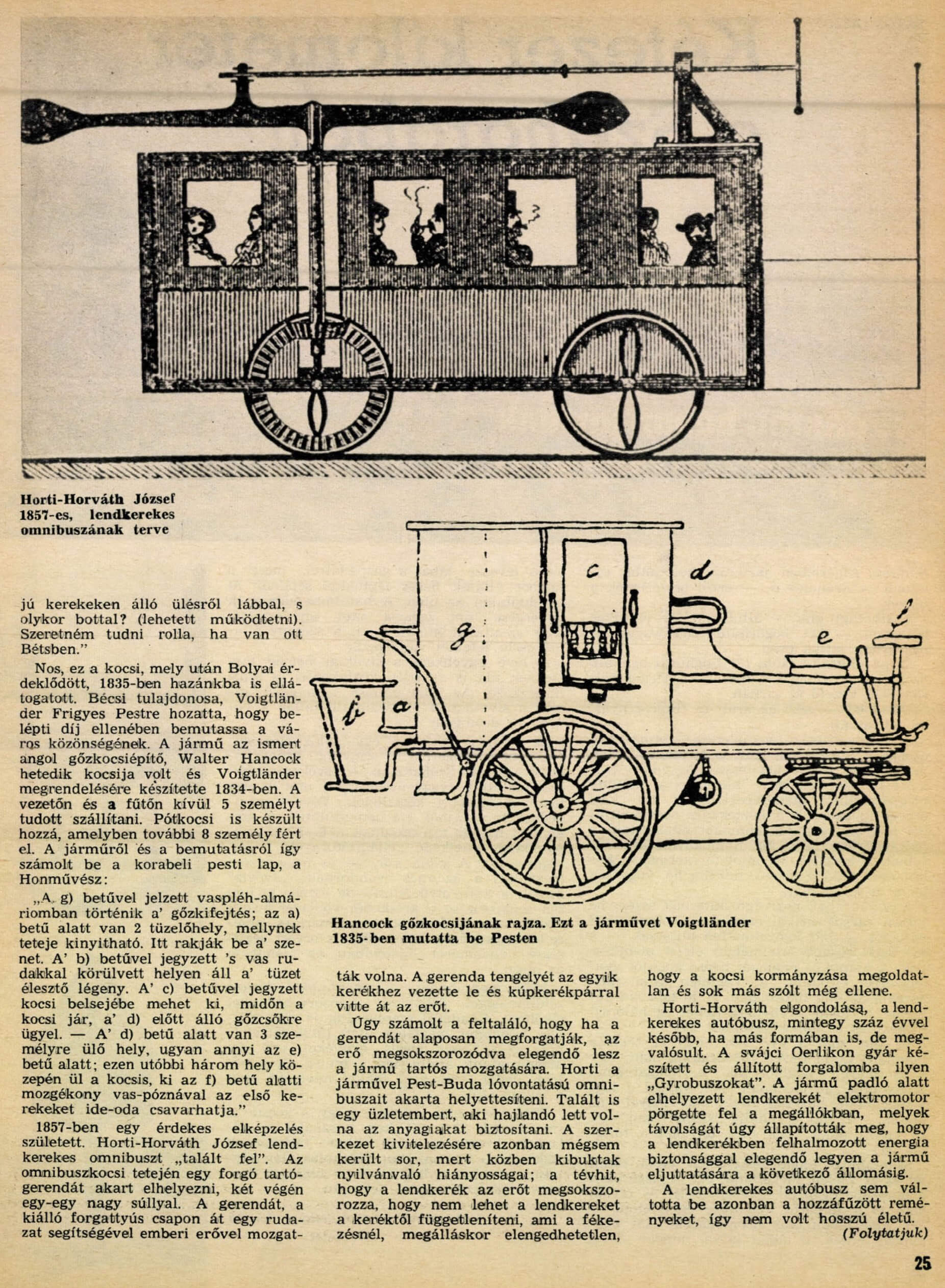

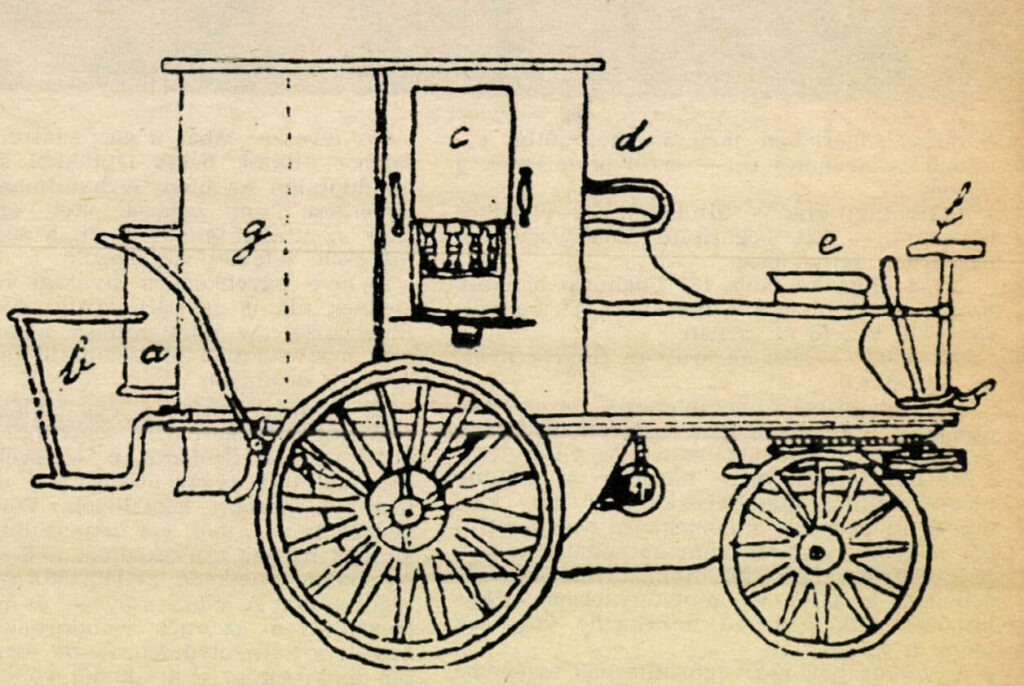

Drawing of Hancock's steam car. This vehicle was presented by Voigtländer in 1835 in Pest.

Well, this carriage, which Bolyai was interested in, visited our country in 1835. Its owner in Vienna, Frigyes Voigtländer Voigtländer, had it brought to Pest to show it to the city's public for an entrance fee. The vehicle was the seventh carriage built by the famous English steam carriage builder Walter Hancock and commissioned by Voigtländer in 1834. It could carry 5 people in addition to the driver and the stoker. A trailer was also built to carry 8 more people. The vehicle and its presentation were reported in the contemporary Pest newspaper Honművész:

"The steam is extracted in the iron-plate almshouse marked g); under letter a) there are 2 fireplaces, the top of which can be opened. This is where the coal is loaded. In the place marked b), surrounded by iron bars, is the fire-breathing air-pen. The carriage marked 'c' can go out into the interior, while the carriage is running, and takes care of the steam pipes in front of 'd.' - Under 'd' there is a seat for three persons, and the same number under 'e'; in the middle of these last three seats sits the coachman, who can turn the front wheels to and fro with the movable iron pole under 'f'."

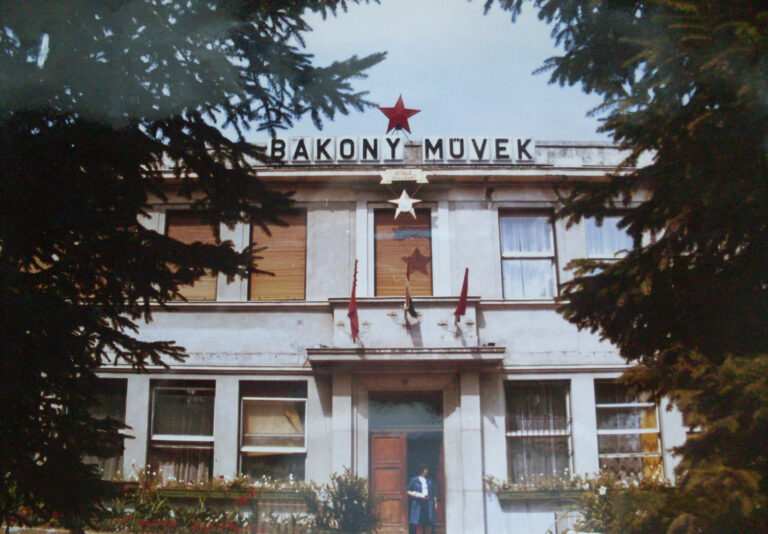

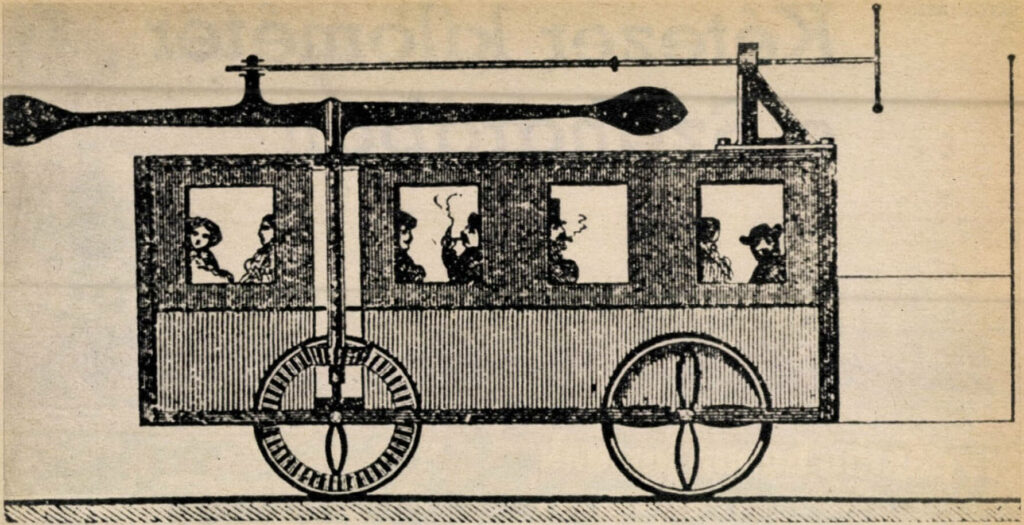

Plan of József Horti-Horváth's 1857 flywheel omnibus

In 1857, an interesting idea was born. József Horti-Horváth "invented" a flywheel omnibus. On top of the omnibus carriage he wanted to place a rotating supporting beam with a large weight at each end. The beam was to be moved by human power through the protruding crank pin by means of a rod. The beam's axle was guided down to one of the wheels and the force was transmitted by a conical wheel.

The inventor calculated that if the beam was carefully rotated, the force would multiply and be sufficient to move the vehicle permanently. Horti wanted the vehicle to replace the horse-drawn omnibuses of Pest-Buda. He found a businessman willing to provide the funds. However, the construction of the structure was not carried out because of its obvious shortcomings; the misconception that the flywheel multiplies the force, that the flywheel cannot be detached from the wheel, which is essential for braking and stopping, that the steering of the carriage is unsolvable and many other things were against it.

Horti-Horváth's idea, the flywheel bus, was realised a hundred years later, albeit in a different form. The Swiss factory Oerlikon produced and put into circulation such "Gyrobuses". The vehicle's underfloor flywheel was powered by an electric motor at stops, the distance between which was set so that the energy accumulated in the flywheel would be safely sufficient to carry the vehicle to the next station.

The Gyrobus G3 bus of the Oerlikon series - image source: wikipédia / Vitaly Volkov, Волков Виталий Сергеевич (user kneiphof)

The flywheel bus, however, did not live up to expectations and was not long-lived.

(To be continued)