1963 - Grand-Prix Budapest

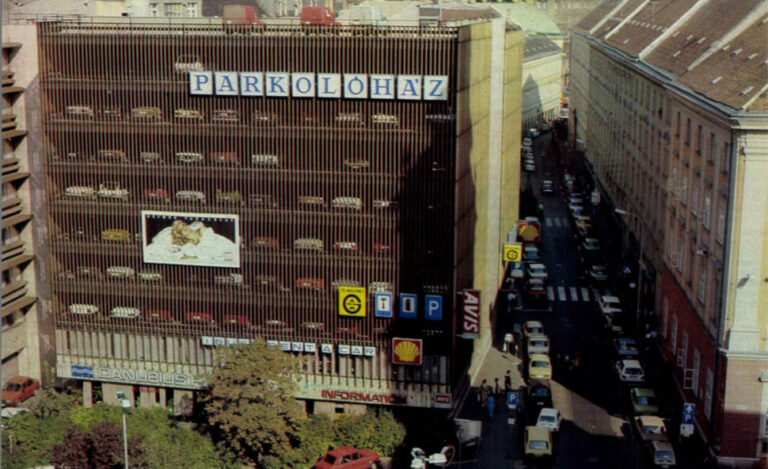

Formula Junior World Championship in Városliget

On 11 June 1961, the Automobile Club of the Hungarian People's Republic organised an international high-speed car race at Ferihegy Airport, where, in addition to Hungarian drivers, renowned foreign competitors also took part. The event was such a success that it was repeated in 1962 and the FIA (International Automobile Federation) based on positive experiences A race in the Formula Junior class was announced for 1963 Nürburgring, Monza, Trier, Monte-Carlo and many other illustrious locations Budapest is. It was the first time in a quarter of a century that such a competition had been held in Hungary, the last time a test of strength for cars was in 1936, when it was held in Népliget, as the first Hungarian Grand Prix.

Budapest, June 7, 1963 - Swedish racing driver Picko Troberg checks his Lola 1963 racing car before the first post-liberation Grand Prix organised by the Hungarian Automobile Club on 9 June at the Stadtligeti circuit. MTI Photo by Sándor Bojár (coloured)

But what was Formula Junior back then?

Formula Junior is an open-bodied formula racing class, first adopted by the CSI (the FIA's International Sporting Committee) in October 1958, designed to provide an entry level where competitors can test their skills against cars built from mechanical parts derived from production cars. Formula Junior was created by Count Giovanni "Johnny" Lurani to give younger drivers the opportunity to make their first their steps, kilometres in the world of single-seater racing cars. It is widely believed that the fact that the Italians were not very successful in the 500cc Formula 3 class at the time was a major factor in the birth of Formula Junior. Accordingly, Italian cars did dominate the first year of Formula Junior, but they were soon overtaken by British constructors.

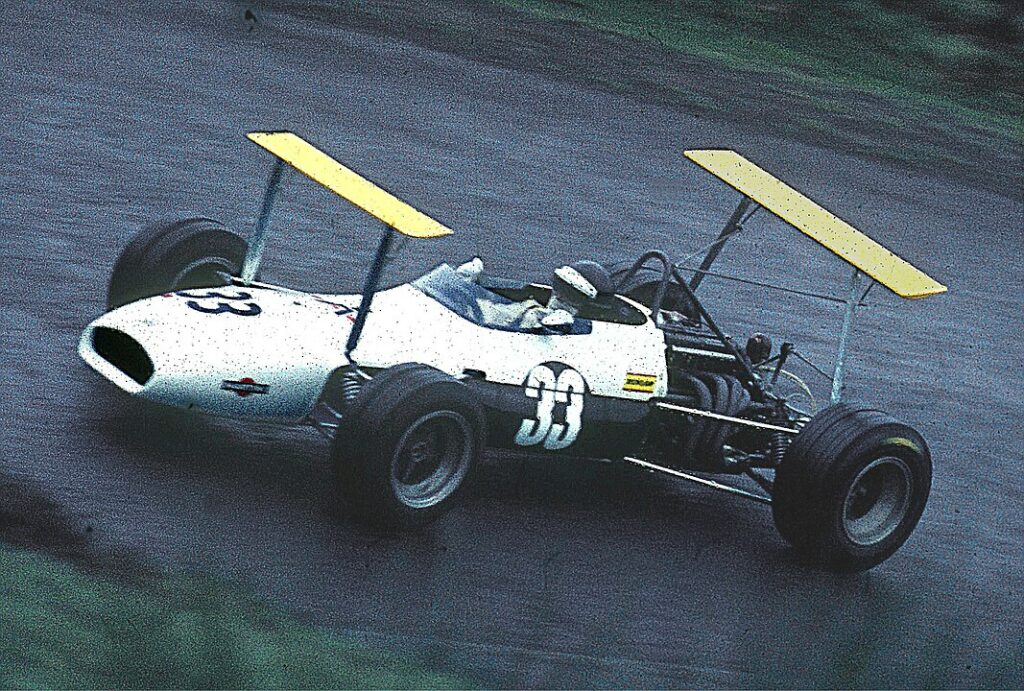

The winner of the Budapest race, Kurt Ahrens, here behind the wheel of an f2 Brabham in 1969. Image source: wiki / Lothar Spurzem

The 4,200-metre course of the Budapest race was laid out along the route Felvonulási-tér - Hősök-tere - Városliget, and the 105 km race consisted of 25 laps. The heats and the finals, held on 8 and 9 June, were held in front of 70-75 000 spectators.

♠

Below you can read the full text of the report published in Autó-Motor on 21 June 1963 by György Rózsa. The pictures, not otherwise indicated, were taken by György Martinecz.

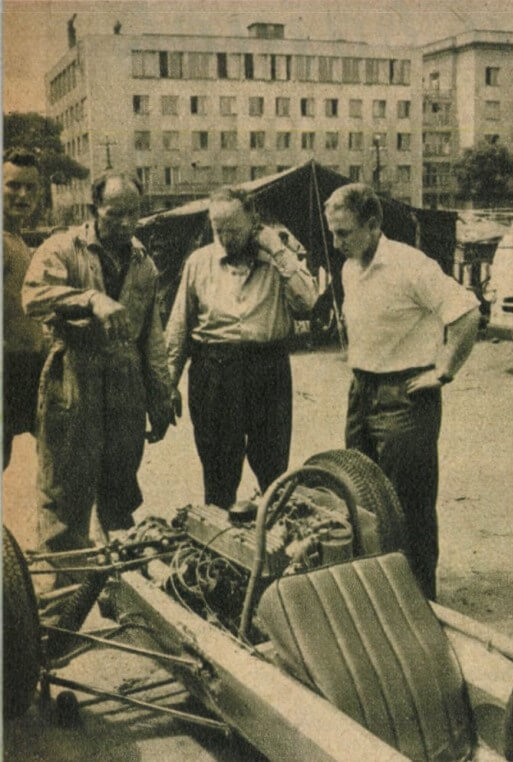

A scene in the pit box during Saturday's training session. There is still work to be done on the engines.

If you were to sum up the 1963 Budapest Grand Prix in one sentence, it would suffice to say that those who missed this colourful and exciting cavalcade of cars would be very sorry.

The Hungarian Automobile Club started early to organise the event and as a result, 38 drivers from 11 nations were able to participate in the FIA-approved GP. In fact, the FIA Presidential Board was so pleased with our 1961 and last year's Ferihegy races that it approved the Budapest Grand Prix as a recognition and added it to its international calendar. Only once before in the history of Hungarian motorsport had such a test of strength been staged; in 1936, the then Automobile Club organised the Formula Racing Grand Prix in Népliget.

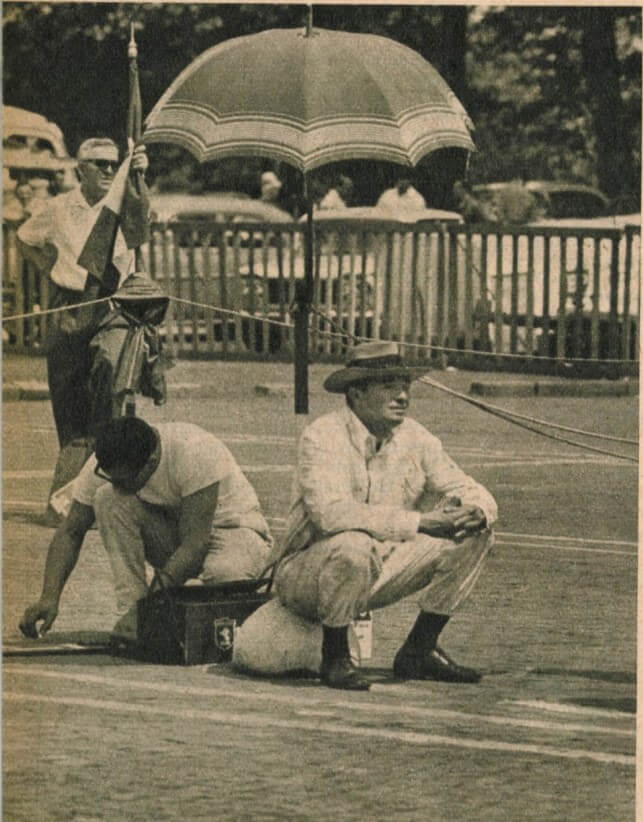

The Ahrens are listening to their chief mechanic's technical opinion about the gearbox of the scratching father's Cooper - which was, after all, dismantled by the owner himself, i.e. Papa Ahrens.

On the day of the training and the technical handover, 8 June, the depot, an almost "airtight" storage facility, was already bustling with life in the early hours of the morning. The exemplary organisation had a beneficial effect. It was possible to keep the crowds away from what was certainly a spectacular area, and partly thanks to this, there was no sign of a rush. Instead of the nervousness that is common in other places, there was a sense of cheerfulness and fun. They towed these ground-sliding, pastel-coloured 'rockets' to the nearby bus garage. Those that did not reach the mandatory 400 kg were loaded with sandbags of the appropriate weight. This was no small task, since these Juniors can only be slid into with the help of a shoehorn, so to speak. (Strange but true, instead of the usual seat, there is a bed, with the rider lying flat on the flat torpedo with his legs fully extended.)

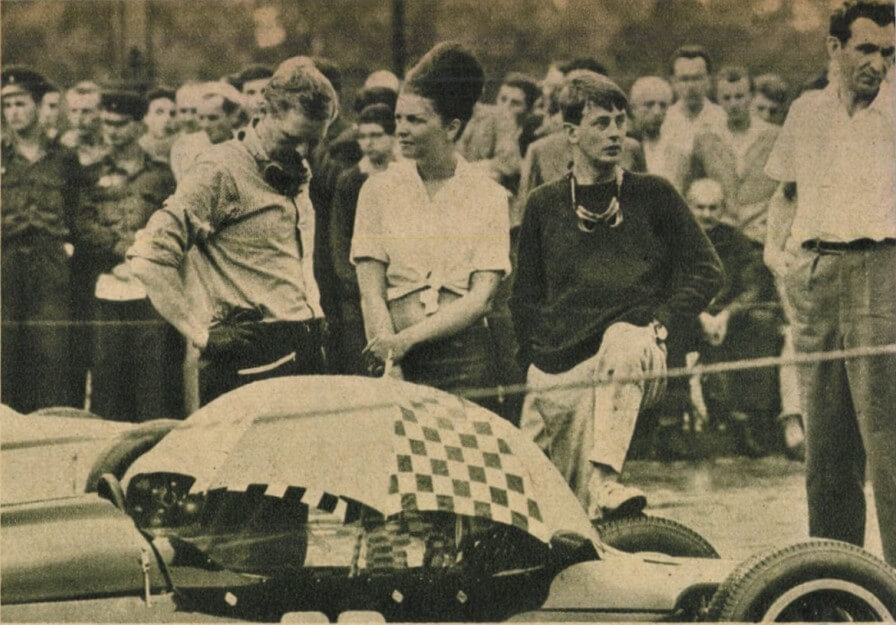

I wonder what the future holds for the final race? - is what Yngve Rosqvist, with his Cooper covered with a coloured umbrella, is thinking. Even his pretty partner can't put him in a better mood. To his right, Frenchman Gabriel Aumont watches his compatriot Calés, not pictured, perform.

ÁFOR's racing service was as active as the fast hands of the service trucks at the Pneumant tyre factory in the GDR. It seemed that the Pneumants were not going to get a place in the depot, on the grounds that we had a rubber industry of our own. The measure was soon withdrawn, fortunately, because Cordatic did not claim this rare opportunity, not to mention the fact that the Pneumant service van's crew, going from race to race, is well equipped and highly experienced. So we had nothing to be ashamed of in this respect either. In other respects, too, we were universally praised: the unanimous opinion of our foreign sporting guests, who attended all the major competitions in Europe, was that the 'insulation' of the storage area from the public and the way the whole event was run was second to none.

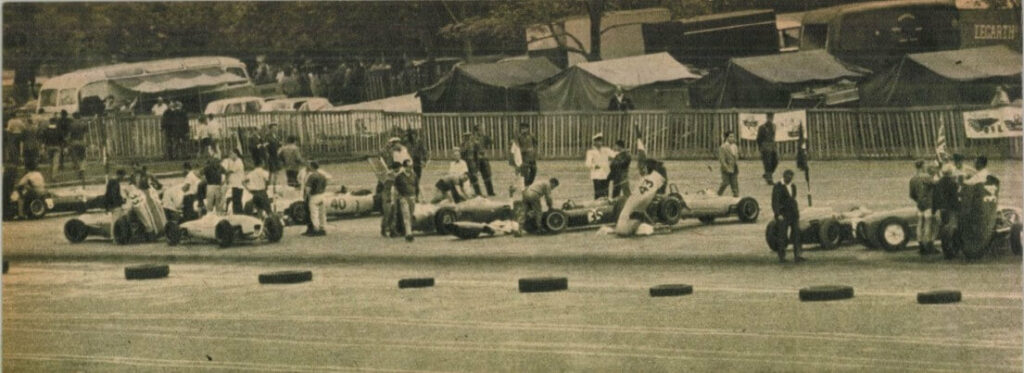

The cars of the first preliminary race were lined up, following the work of the start preparers. This will be the front row.

On Saturday afternoon, the sky was overcast when it was time to "taste" the 4200-metre cunning track. The monumental parade ground was filled with a healthy herd of 1,500 to 2,000 bred, "technical" foals. Each race allowed 15-20 cars, with an average power of 100 horsepower. After a few laps, the picture of the next day's race began to take shape. It was certainly no small task for those who would be challenging the winners of the last two races, the Finnish Lincoln, the German Ahrens, the balsorst-chased Bardi-Barry from Vienna and others. Because they dominated the field this time too.

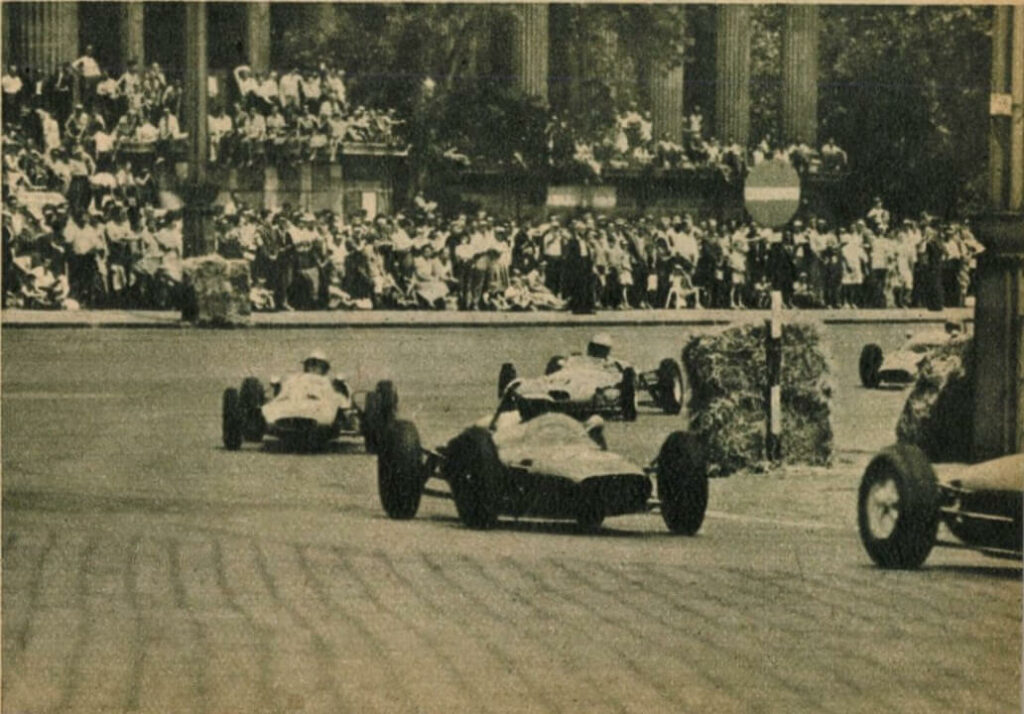

The picture was taken shortly before the start of the first heat.

The Austrian timekeepers, with their special Omega electrical equipment, were at the service of the Hungarian Automobile Club. (By the way, can we get one of these devices? Of course, the "partner" sports could also make very good use of it!) Well, according to the timekeepers, the fastest was Bardi-Barry with a lap time of 2.01, which is equivalent to 125 km/h. Behind him was Lincoln, Jr. Ahrens, Sweden's Troberg and Rosqvist and the Czech rider hiding behind the pseudonym "Müller". In 14th place was the Polish driver Jankowski with his old three-year-old Wartburg, 19th Melkus, 20th Lehmann, 28th Ferenc Kiss, 33rd István Sulyok. Tibor Széles didn't get far with his "freshly baked" Melkus-Wartburg, only to Heroes' Square, where, as he later explained, he hit a lamppost because the engine refused to "rev". And all this happened in the bend, where the wheels could have been driven to avoid the unfortunate slip. Fortunately, Széles was unhurt. But there was no time to repair the damage to the new car.

They're waving off the runners in heat II, Lincoln with his hand raised to indicate his intention to stop, alongside the already beaten Frenchman de Laforest (20)

Then came the draw for the two heats of the next day's race, which promised much good news, as the two Ahrens were joined on the same row - from the front row, of course - by Barry and Rosqvist.The two Ahrens tried to appeal their joint start, but there was no room for appeal, so the son had to fight his father.

In glorious weather, the young Ahrens' Cooper was the best starter on the course, which was watched by about 60,000 spectators, and he took off like a bullet, followed by his black Cooper, Rosqvist, who was also in the lead. The secret favourite, Barry, gave chase with a similar Cooper. He was in 2nd place, but fell back again and eventually dropped out. It wasn't until much later that the audience learned that what was to have been a magnificent duel had been abandoned because Barry's car's gearbox had broken on lap 6 - causing no small scare for the others with oil spilling on the road. "Little" Ahrens was a sure winner. In addition to him, the following seven runners-up from the heats went through to the final race: Rosqvist, Mattila (Finland), Schramm (NSZK), Ellekär (Denmark), Meub (NSZK), Melkus (GDR), id Ahrens. (Fastest lap: Ahrens jr. 123.7 km/h; Melkus' best time 121.0 km/h.)

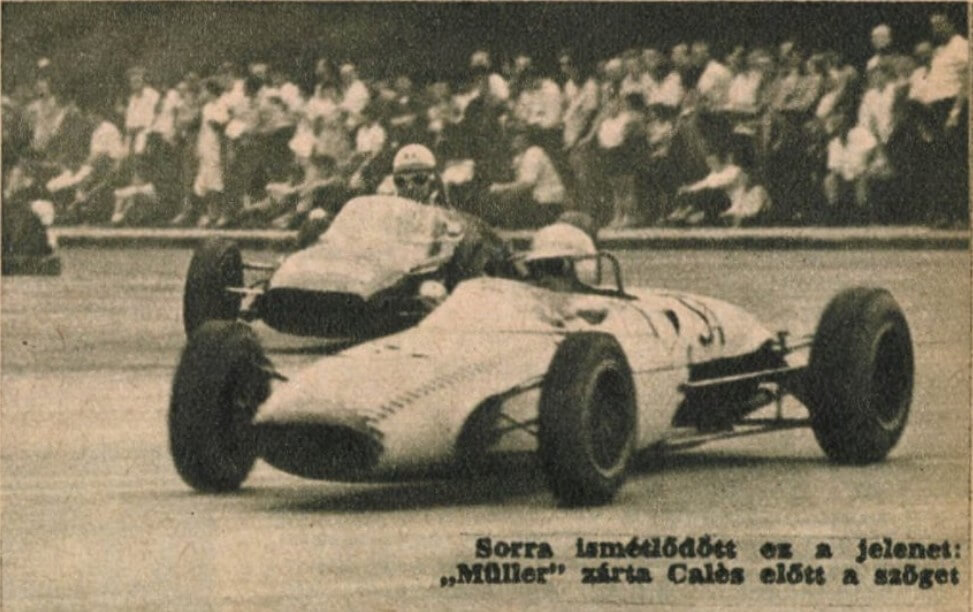

The second qualifying race also provided a treat, although it was going to be a "lukewarm" one, as Lincoln - apparently - had no worthy opponent in this field. But fate had other ideas. The leading Finn's snow-white Cooper spun on Barry's oil slick, which Lincoln masterfully avoided, but the manoeuvre sent him back to the front. What followed was almost eye-catching. The Finnish champion set an increasingly ferocious pace, oblivious to the black clouds over the City Park and the drizzling rain. This was the fastest lap of the race, 124.3 km. But there was a fierce battle for places further back. The first surprise was provided by Austrian Jochen Rindt, who gave his rivals a run for their money in a Lotus borrowed from the Italians (a rare talent for this 21-year-old, who was in his sixth race.) In what our Polish friends had hardly expected, engineer Jankowski was holding his own in 5th place with his stalled RAK-Wartburg, until his car 'danced' on a puddle of mixture that spilled from the tank of a two-stroke car. This unexpected interlude was enough to 'suck' his engine dry, and by the time it had 'picked up' speed again, the others were whizzing past like arrows. A heated "debate" ensued between the Frenchman Calés and "Müller", so much so that the temperamental French champion finally expressed his disapproval with an unmistakable claw gesture.

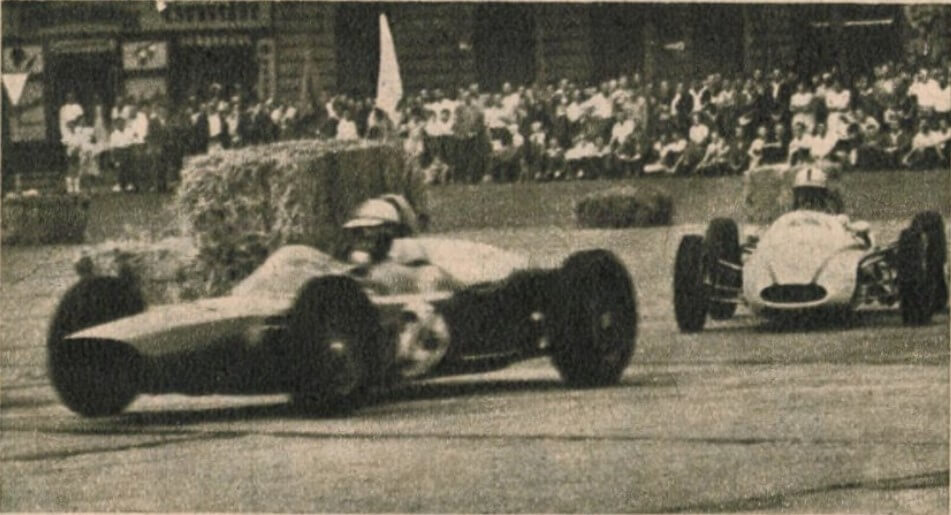

The recording above captured an interesting scene. Rhodesian David Riley, starting from the right corner, is about to cut in front of the elder Ahrens in his white Cooper, not quite regular.

The pseudonymous German's Lola-MK was faster on the straight than Calés' Stanguellini, who tried to compensate for this technical disadvantage with his artistic cornering, but "Müller" did not quite "close" the corner cleanly. Meanwhile, the leading Swede with the big moustache, Pico Troberg, was steadily making his laps and, as the signals from the pit box indicated, he rode his Lola engine to the finish line as the winner. His average was 115.6 km/h. The other finalists, in order of finish, were Lincoln, Italian Francesco Franzan, Rindt, "Müller", Calés, Danish Christian Legarth and Austrian Sklenar.

Taken at the Museum of Fine Arts in Heroes' Square during the 2nd preliminary race. In the front is the Danish Legarth in his Lotus, behind him the Polish Jankowski, the French Aumont (Lotus), the GDR Lehmann (99) and the French de Laforest.

The next quarter of an hour praises the audience. The heavens have opened, but very, very wide. Despite this, the fans held on faithfully, defying the heavy sky. And the reward they deserved was not missed: a series of events of unparalleled interest and excitement.

A high curtain of water was drawn behind the wildly overspeeding wheels, like a speedboat race. Oh my God, what's going on!? This race could be a menace not only to the modern champions, but also to the spectators. But fate had mercy on the Budapest Grand Prix, because apart from a few broken cars, there were no other problems.

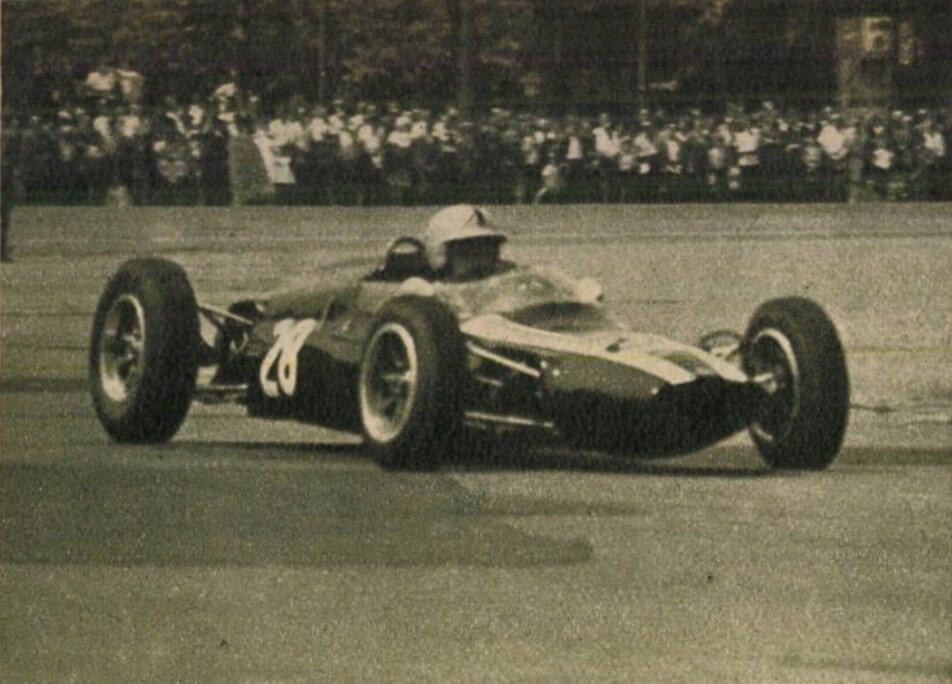

On the way to winning the heats (Ahrens Jr.).

The first few metres already got me in the right mood to get my nerves on edge. Cars were spraying from Heroes' Square (but that's to be taken literally) when the elder Ahrens, one of the front runners, was unable to keep his black Cooper straight, which swerved right like a bull. Like lightning striking a flock, those close behind tried to jump him (the pace was 80-100 km). At the edge of the track, the more nervous covered their faces, the braver ones fell over to find cover. The car's wheels were already drawing a full circle on the rain-soaked ground when the Cooper, which had been pushed into the road, started to spin in the opposite direction. All it took was a fraction of a second, and that flash of time was too little for the Dane Jörgen Ellekär, who was trying to sneak past Ahrens on the right. With a silent thud the wheels crashed and the black Cooper was stuck with its front end smashed in. It was not long before the red Lola was in a better position. That's how they ended up on the pavement.

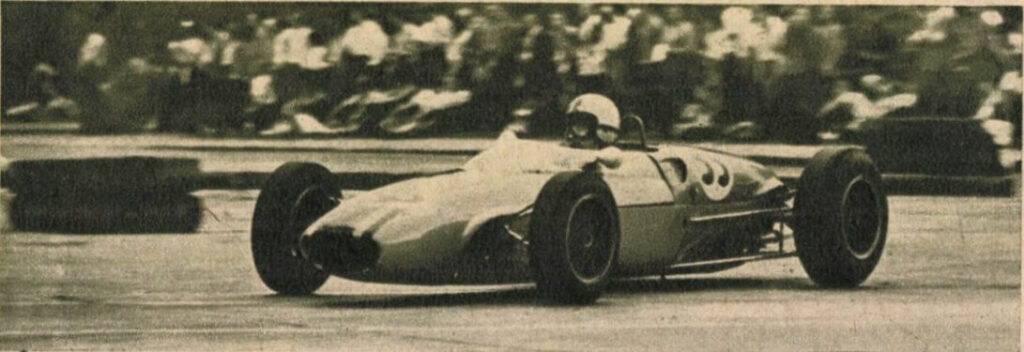

The deserved winner of heat II, the Swedish Pico Troberg on the straight on Dózsa György út. His yellow-painted Lola reaches a speed of 200 km.

Put your hands on the heart of any reader who can drive a car and can keep a 400 kg torpedo propelled by a 100 hp engine on such "unstable" ground. It is not a bend we are talking about, but the straight on the Dózsa György road, where these cars have reached speeds approaching 200 km. Here, for example, is the Italian Franzan, who, perhaps with a thought, stepped on the accelerator a little harder and the Lotus was already a carousel. But Franzan wasn't intimidated by her shadow; when the nose of her car pointed straight ahead, she stepped on the accelerator, but now in a miss - and the Lotus continued on its way like a handmaiden.

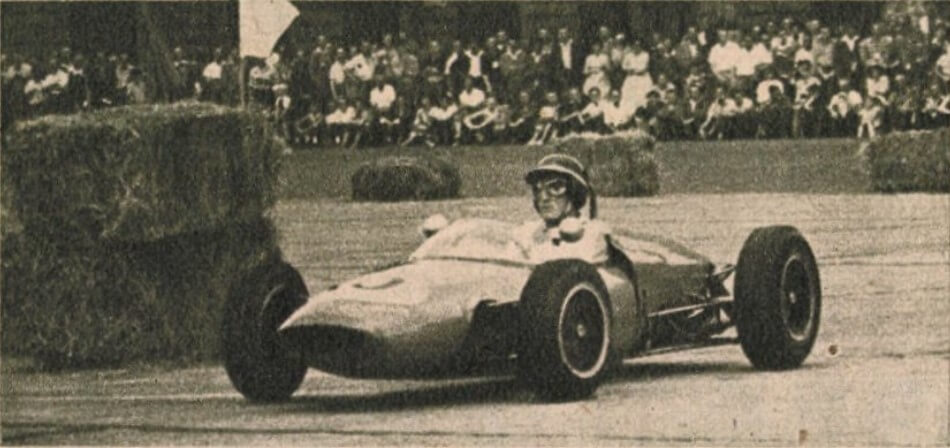

In the Lotus car borrowed from the Italians, the Austrian Rindt, a rare talent, ran a great race.

The younger Ahrens took the corners with courage and smoothness. Behind him was the promise of the future, the Austrian Rindt, racing his now repaired black Cooper. Far behind him was Rosqvist, followed by the once also scorched Lincoln. The race-winning Troberg also had the "giddiness" of the race, cutting a quadruple pirouette that any famous ballerina would be proud of. That's how she got to the end of the line.

The difference of about 25-30 hp between the RAK-Wartburg and the Cooper was noticeable. Here Lincoln is about to overtake our friend Jankowski.

And Rindt? He was closing in on the leader until a soft crack - and the roar of the engine - signalled the end of a promising race for him. The Cooper's right half-shaft had broken. That put Lincoln in second place, having overtaken Rosqvist - or rather, the three of them had lapped the whole field - some more than once. In addition, just six of them had stopped in their pits and were unable to continue the race. Heinz Melkus was one of them.

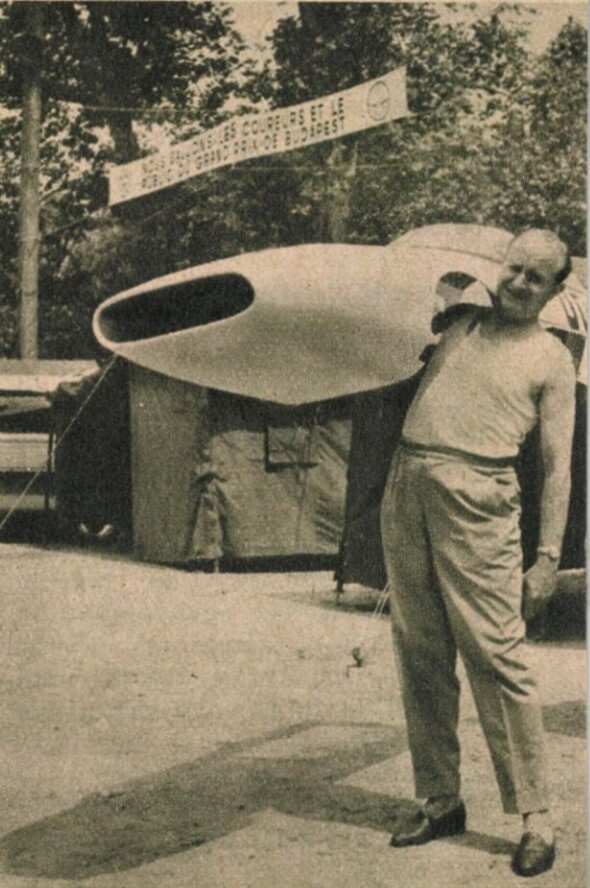

S.E.G.-Wartburg driver Willy Lehmann holds the polyester body of his car as if it weighed 50 kilos, not 2 kilos.

Nobody doubted Ahrens Jr.'s victory. Because those who, because of their younger age and blood density, might have risked more than necessary - namely Rindt and Barry - were no longer in the "deck", and so the winner of last year's race car race roared to victory without danger.

The Italian pit crew was a real southern bunch. The race is not yet underway, but the text of the "secret" signal is being drafted.

RESULT: 1, K. Ahrens jun., K. Lincoln, Finland (Cooper) 56,48.85, - 3. Y. Rosgyvist, Sweden (Cooper) 58,39.72, - 4. ,F "Müller", Germany (Lola) 1 lap down, - 5. F. Franzan, Italy (Lotus) 2 kh, - 6. J. Calés, France (Stanguellini) 2 kh, - 7, P, Meub, NSZK (Cooper) 2 kh, - 8. L. Mattila, Finland (Lotus) 2 kh.